There are examples everywhere. Last year, the California auditor's office issued a report that looked at accounting records at the State Controller's Office to see whether it was accurately recording sick leave and vacation credits. "We found circumstances where instead of eight hours, it was 80 and in one case, 800," says Elaine Howle, the California state auditor. "And the system didn't have controls to say that's impossible." The audit found 200,000 questionable hours of leave due to data entry errors, with a value of $6 million.

Mistakes like that are embarrassing, and can lead to unequal treatment of valued employees. Sometimes, however, decisions made with bad data can have deeper consequences. In 2012, the secretary of environmental protection in Pennsylvania told Congress that there was no evidence the state's water quality had been affected by fracking. "Tens of thousands of wells have been hydraulically fractured in Pennsylvania," he said, "without any indication that groundwater quality has been impacted."

baddata-infographic-thumb.jpg

But by August 2014, the same department published a list of 248 incidents of damage to well water due to gas development. Why didn't the department pick up on the water problems sooner? A key reason was that the data collected by its six regional offices had not been forwarded to the central office. At the same time, the regions differed greatly in how they collected, stored, transmitted and dealt with the information. An audit concluded that Pennsylvania's complaint tracking system for water quality was ineffective and failed to provide "reliable information to effectively manage the program."

When data is flawed, the consequences can reach throughout the entire government enterprise. Services are needlessly duplicated; evaluation of successful programs is difficult; tax dollars go uncollected; infrastructure maintenance is conducted inefficiently; health-care dollars are wasted. The list goes on and on. Increasingly, states are becoming aware of just how serious the problem is. "The poor quality of government data," says Dave Yost, Ohio's state auditor, "is probably the most important emerging trend for government executives, across the board, at all levels."

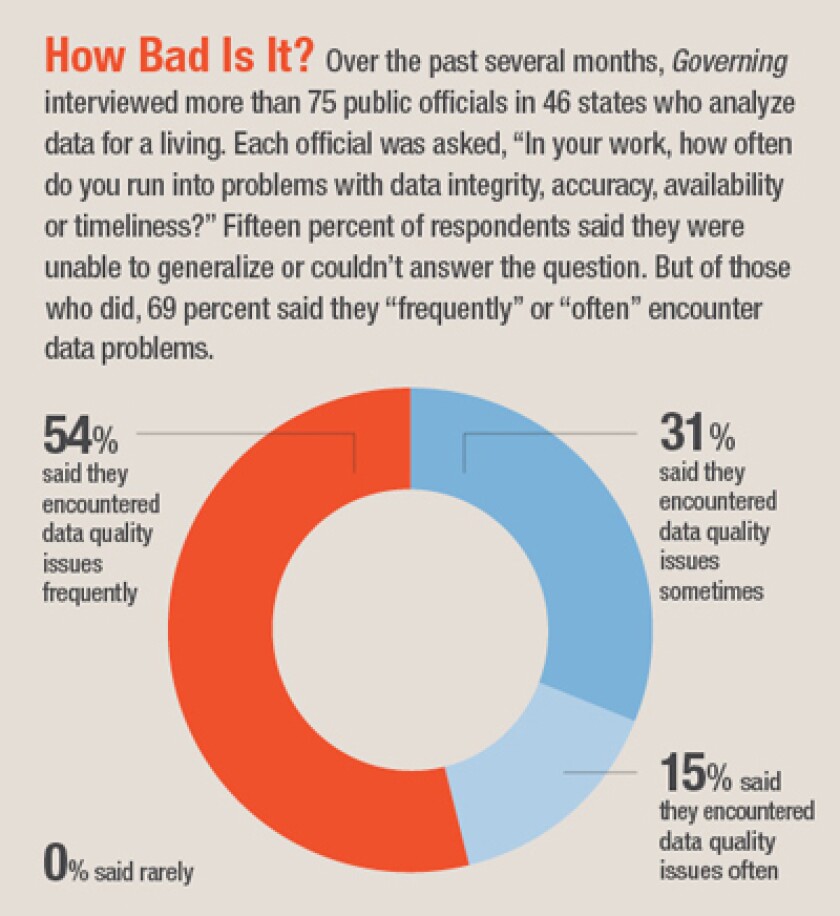

Just how widespread a problem is data quality? In a Governing telephone survey with more than 75 officials in 46 states, about 7 out of 10 said that data problems were frequently or often an impediment to doing their business effectively. No one who worked with program data said this was rarely the case. (View the full results of the survey in this infographic.)

How often do you run into problems with bad data in public-sector agencies?

It's not that data, in general, is worse than it was in the past. Not long ago, huge quantities of data existed only in warehoused file cabinets; technology has changed that for the better. But our dependence on data has increased dramatically and the problems caused by poor information have expanded as well. "In an age of Google and with the advent of big data on the Internet," says John Traylor, New York's executive deputy comptroller, "expectations for data have gone up. People are asking questions that they didn't ask before."

Most of the data problems are in program management, not in financial accounting. Traylor says he has accountants who are "trained in a discipline that places a high value on peer review, internal controls, edit checks -- all the stuff that accountants want to do. In the programmatic world, you have program administrators who don't have that type of training. Their disciplines are focused on getting data out quickly or looking at it quickly."

That's a problem with a lot of dangerous implications. At all levels of government right now, there's an intense focus on collecting information and using it to drive decision-making. Call it the gospel of data: the sense that predictive analytics will solve all problems, all of the time. In many ways, that's true. Data analytics can be a powerful tool to help governments run more efficiently and effectively. But data analytics are only as good as the data itself. As states and localities focus ever more intently on information gathering and analysis, there's a crucial question that frequently isn't being asked: How good is our data?

Generally, how would you rate your own agency’s data?

The Pain of Bad Data

When states can't come up with the appropriate data -- or simply rely on bad data -- it's a lot like trying to drive a car with an empty gas tank or like putting salt in the gasoline. For example, the Railroad Commission in Texas is responsible for the regulation of oil and gas development. It tracks violations of the rules, and its data showed that 96 percent of cases were closed with no enforcement action. That would lead policymakers to the conclusion that the vast majority of cases were without merit.But there was a hitch. There was no effort to link the violations with companies to see if problems were recurring. One company could be cited 10 times, and only be subjected to enforcement actions the 10th time. "They had no idea whether the same company was recidivating -- committing similar violations over and over. We requested the raw data and put it together," says Ken Levine, director of the Texas Sunset Advisory Commission, which reviewed the Railroad Commission's work for the state legislature in 2011. "We showed that they were doing a poor job of ensuring enforcement was done at a level that would deter future bad acts."

The agencies with the worst problems in many states are those involved with social services and economic development. Weaknesses also often show up in small units of government -- those with inadequate IT skills and very decentralized agencies that are heavily reliant on local administration of state services. "When there are lots of people with their hands on the data," says Dianne Ray, state auditor of Colorado, "that's where we find the biggest problems."

On the positive side, programs that are partially funded by the feds tend to be richer in data than most others "because the federal government requires it," says Carrie Vibert, who runs the Connecticut Office of Program Review and Investigations. Most state transportation agencies handle data fairly effectively because they are required to report a plethora of information to Washington. "Transportation measures things because it's run by engineers who like to count," says John Turcotte, head of North Carolina's Program Evaluation Division. "They collect very good data."

In many agencies, however, it isn't a question of good or bad data. There isn't any usable data being collected at all. In Massachusetts, for example, there has been a great deal of debate over the value of charter schools. The state auditor's office planned on issuing a report late last year that would help lay some of the more contentious debates to rest. But that never happened. There was so little reliable information being gathered that the state was simply unable to come to any useful conclusions.

Neighboring Connecticut offers another troubling example: The Rocky Hill Veterans Home, which provides housing for homeless veterans. One of the goals of the program was for residents to exit the home within three years. But for a long time, nobody knew -- or could possibly know -- if the goal was being achieved or not. That's because there had been no usable data collected, except in individual files, on how long people actually stayed. And since no one was going through the individual files one at a time, the aggregate numbers weren't available.

When reviewers decided to look into this issue, they did their own survey of veterans in the home. It turned out that about 60 percent of the residents had lived there longer than three years and about half had been there at least five years. When asked about the help they had received from the staff in finding permanent housing, only 10 percent said they were satisfied.

And consider West Virginia's river gages. The state has a goal of ensuring that 90 percent of its gages, which are used to measure water levels, are operating properly. The Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management offered up 2012 data showing that some 93 percent of the state's gages were functioning as intended. That was an encouraging number. But when the agency was asked for documentation, it turned out there was none. According to John Sylvia, director of the legislature's Performance Evaluation and Research Division, the figure was based on "visual estimates and memory" of the communications officer.

West Virginia officials based its water-level measures on “visual estimates and memory.” (Flickr/Dion Hinchcliffe)

Why There's a Problem

In order for governments to address the issues of bad or nonexistent data, they need to understand the underlying causes of both. In Massachusetts, for instance, the technology systems are so old and clunky in the Department of Families and Children that social workers stopped inputting all of the records into them. It's just too time consuming.In Alabama, the use and analysis of data is thwarted by early 1990s technology. "There are limitations to our old system that have made it very difficult to analyze data and extract the data. That's been a hindrance here," says budget officer Kelly Butler.

But the age and capacity of the technology is only a part of the problem; and one which is difficult for many states to alleviate in a time of fiscal stress. There are a number of other critical failings that have blocked the most effective uses of data. The list is long and includes error-filled data input, ineffective system controls, untrained workers, inconsistent definitions, siloed systems, lack of centralized control of data and problems with data collected by private-sector contractors.

Siloed Systems

In many states there is minimal sharing of data between technology systems that are run by separate agencies or even separate programs within the same agency. In Louisiana, for example, there has been resistance to building data warehouses in which data could be shared. "Everyone is proprietary over their systems," says Catherine Lyles, a senior auditor in the state.The disadvantages of such data silos are many. Most obviously, the ability to coordinate services is limited. Shouldn't the mental health department, for example, know what's happening to someone who is receiving mental health assistance within the Office of Aging and Adult Services? And vice versa?

One reason often cited for a resistance to sharing is that state or federal laws mandate privacy for individual pieces of data. This is valid in some cases, but when state attorneys general look into the situation, they often find fewer legal impediments to sharing data than they anticipated. It's just a handy excuse.

Massachusetts' state auditor, Suzanne Bump, has a skeptical take on why some agencies are resistant to sharing their data.

In her view, these agencies don't want to share simply because they don't want to reveal how little they understand about the data they keep.

The Rocky Hill Veterans Home in Connecticut, which wasn't collecting usable data on how long people were staying. (CT Monuments.net)

Bad Definitions

In state agencies that depend on multiple sources of data -- such as local governments, school districts and regional offices -- a tenacious effort has to be made to ensure that all data collectors are gathering the same information in the same way and using the same definitions. The most obvious mistakes involve names and addresses, which are often input differently if naming conventions are not thought out in advance. "Are you dealing with the same Bill Jones, William Jones, Billy Jones, Bill A. Jones and so on?" asks James Nobles, Minnesota's legislative auditor.The lack of solid definitions often compromises the meaning of the information collected. During the recession, the Pennsylvania Legislative Budget and Finance Committee looked into the effectiveness of the state's Keystone Opportunity Zones program using a survey of businesses that was generated by the program itself. But though the gist of the issue was "jobs," the survey didn't identify that word adequately. Philip Durgin, executive director of the committee, says there was no explanation of whether the number of "jobs created" was a cumulative total or a total for one year or whether part-time and full-time jobs were to be treated in the same way. "That wasn't specified," he says. "Some reported anticipated jobs. Some reported jobs created in a single year, while others reported jobs created since joining the program. The whole common definition thing was a huge problem."

One state that has set about unifying its streams of data is Utah, which has labored to make sure all the different parts of government understand financial information in a consistent way. State officials are now working on reaching a similar level of understanding about program data. On the financial side, it has a chart of accounts that is shared across all three branches of government as well as the school system. "We're using a common set of definitions," says Jonathan Ball, a legislative fiscal analyst.

Third-Party Issues

When government services are privatized, often the data available on performance is greatly diminished. Bruce Myers, the longtime Maryland auditor who retired in 2012, often warned about data problems when governments deal with third parties, such as contractors, other levels of government or school systems.Contractors specifically tasked with reviewing or analyzing data may stumble in their efforts to communicate the information adequately. In the simplest of cases, New Jersey county officials were unable to use four of the six major data reports that pointed out instances of possible food stamp fraud, because the state's vendor, which was responsible for providing this information, did so in a format unusable by the counties.

The third-party problem is particularly significant in Medicaid managed care. A Government Accountability Office report released a year ago pointed out that neither the states nor the feds have strong data on improper payments in managed care because just about all tracking efforts are geared to traditional fee-for-service systems. The report also noted that claims information in Medicaid managed care can be difficult to obtain and often winds up in a kind of "neglected data middle ground" between information collected at the federal and state levels.

Ineffective Controls

Controls may be built into a technology system, but it's not uncommon for employees to shut them down in order to get things done more quickly. Or they might subvert them in other ways. For example, a computer form might not allow a worker to move forward without a Social Security number, and rather than delay an application, employees resort to the expedient solution of listing participants as having a Social Security number of 999-99-9999.This has been the case in New Jersey's Department of Human Services. "They do it to move through but then don't come back and fix it because it's not important to the program person," says state auditor Stephen Eells. "But the data has no integrity."

The common use of spreadsheets as a repository for data adds to control issues. Numbers stored in Excel or other similar programs are very easily changed as time goes on; as a result, there may be no older number that can be used for analysis or to compare with the current number in order to pick out outliers. "It's easy to replace numbers but you lose history," says Virginia's Nathalie Molliet-Ribet, deputy director of the state's Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission. If the number of jobs that have to be created in an economic development deal is changed from 300 to 100, the original number will just be replaced, and the fact that there was a change will be lost.

Undertrained Workers

When people talk about data flow, an image emerges of rivers of words and numbers being transmitted smoothly and speedily from one computer to another. There's something missing in that picture, however: the flesh-and-blood human beings who manually put information into the system. In a variation on the cliché "garbage in, garbage out," John Geragosian, auditor of public accounts in Connecticut, likes to say that "data is only as good as how it was input."There was the case of a data inputter in Oregon who filled out a payment field for an invoice of $323.88, but mistakenly put the federal ID number in the payment field instead of the amount owed. Federal ID numbers are long. So a check was written and mailed for $1,748,304.24. If that wasn't bad enough, this number had to pass through a supervisor before the check was sent, and he, too, was asleep at the data switch. The average payment going out was less than $3,500, so a check in excess of $1 million should have been more than a red flag -- it should have been a luminescent display of fireworks. Fortunately, the state did get its money back when the error was exposed.

Problems with inputting and using data are particularly common because the men and women who are hired to do the job aren't necessarily well trained in data management. Often they don't have any mental filter to alert them when a number appears incongruous or at odds with common sense. Says Texas' Ken Levine, "You have a lot of people who are extremely low-paid whose jobs are to get the data input as quickly as possible."

Like most states, Massachusetts uses a contractor to provide reports on the data generated through the use of electronic benefit cards. The contractor provides monthly data reports to track unusual patterns of benefit usage -- for example, Massachusetts food and nutrition benefits used outside of the state. Agency staff had the capacity to use this information to detect potential fraud, but "we were told they didn't know how to read the reports that their system had been generating for years," says state auditor Bump.

Even when there's an original intent to provide adequate training, it can sometimes disappear in the dark of a late afternoon budget session, when a technology project appears to be running over budget and behind schedule. Says California auditor Howle: "If a project is behind schedule, the project management that gets cut is training. There's not enough training before a system is rolled out and that's typically where you see problems. Training is where things get cut way back. It's not nearly as robust as it should be."

More Access, More Vulnerability

Says Connecticut auditor Geragosian, "A lot of our concerns have to do with permissions that are overly generous within agencies -- the ability to manipulate data [should] only go to the appropriate person and there should be a separation of duties."A New Jersey audit of the Department of Human Services found data was potentially compromised by a large number of employees who were characterized as "super-users" of the computer systems. These 65 individuals had the ability to sign on to the computer, create electronic benefit accounts, issue benefit cards and put money on those cards -- duties that most auditors and accountants would agree should have been kept as separate and distinct.

What is at the root of your bad data?

Looking for Answers

Some of the solutions to bad data issues involve spending money to replace and update ailing technology systems. There is also the need for more data scientists and analysts in government, a potentially expensive proposition given the demand that the private sector has for these individuals as well.But many other solutions can work because they don't rely on a heavy investment of new dollars. The list starts with providing better definitions of what computer fields mean, creating data inventories so that states know what information they have, building system controls to prevent inputting errors, making sure that workers who are inputting data are trained and supervised, and teaching managers to use the data they receive in reports from vendors.

Creating or improving data governance can also be of help. In most states, the chief information officer is responsible for the technology itself, but that doesn't translate to responsibility for data quality. Several auditors and evaluators mention that technology officers regard data quality and accuracy as a topic that lies outside their sphere of responsibility. "They don't think their role includes how consistent the data is or being able to use the data," says one. That leaves it up to the agencies to figure things out for themselves.

Fortunately, there is a movement to formalize data governance in some states. According to the Council of State Governments, as of July 2014, seven states had chief data officers: Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Maryland, New Jersey, Texas and Utah. New York's deputy secretary for technology also functions as a chief digital officer and legislators in California are considering creating a chief data officer position.

Finally, before spending money to collect data, states should consider the whole range of agencies that can possibly use that information, beyond the single one that's actually collecting it. For instance, Virginia gathers a great deal of information about its personal income tax, which accounts for 57 percent of its revenue. It collects very little data about its corporate income tax, which accounts for only 4 percent of revenue. The imbalance of information might make sense if you were thinking only about the taxes. But the data collected via corporate taxes could also be very useful for the state's economic development efforts.

As states struggle to improve the reliability and utility of their data, there will always be question marks following the assumptions used to derive it in the first place. But it's worth the effort. Consider the words of Arthur C. Nielsen, founder of the market research firm that churns out some of the most sought-after data on the planet. "The price of light," Nielsen said, "is less than the cost of darkness."

This column was originally published by Governing.