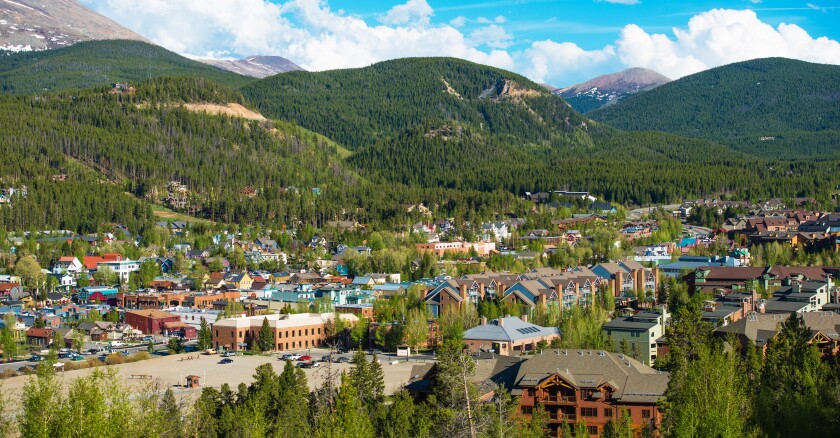

Summit County, Colo., knew as early as 2018 that big changes were afoot in terms of homeownership and residency patterns. The county includes Breckenridge, one of the country’s most popular vacation destinations. Complaints started to come from locals concerning land use, noise and garbage in certain residential areas with a high concentration of short-term rentals (STRs). These changes also drove environmental problems when occupancy in a house would balloon; in one community, the high number of STRs even led to wells going dry. According to County Commissioner Elisabeth Lawrence, the county wanted to address these issues through regulation but did not have the necessary data.

Lawrence worked with Sally Bickel, Summit’s GIS engineer, who played a critical role in gathering data and identifying issues. “We needed to show the state, our lawmakers, why it was so important for us to have the ability to license short-term rentals — and eventually, last year, to have taxing authority as well,” Lawrence said. “We needed to understand better what was happening.” The initial GIS exercise showed that some neighborhoods moved from 10 percent short-term rentals to 27 percent in less than 18 months.

The county established an STR-specific position, now held by Brandi Timm, the STR program coordinator. Timm and Lawrence used the GIS data to address the complications of Summit County becoming a hotbed for short-term rentals, which has both pros and cons. Lawrence and her fellow county commissioners did not have any interest in eliminating STRs, but wanted to regulate them in a way that didn’t tip the quality of life in a neighborhood. Rentals can drive up housing prices, affect home availability and put stress on residential communities. The Summit County team explained that the housing price jump was so extreme that a home purchased in 2019 for $500,000 would cost a million dollars by 2021.

Nevertheless, the officials emphasized that they understand that their tourism brand means both accommodating visitors and supporting housing for those who work in the county and provide services to those visitors. Property rights advocates lined up on both sides of the issue, with one group saying, “This is my home that I live in full time. And now I’m living next door to a mini hotel and the rentals have changed the character of my neighborhood,” while the other group asserted their right as homeowners to rent short-term.

These difficult issues are best balanced when high-quality data is well visualized. Bickel’s ongoing GIS work helps land use planning while also assisting Timm with her regulatory responsibilities. New ordinances require that property owners and/or managers obtain an STR license prior to advertising, and the county can now impose a cap on the amount of STRs in each of the county’s four basins. For example, the Upper Blue Basin will have a cap of 590 STR licenses, which equates to roughly 18 percent. Although most neighborhoods are currently above this limit, the city won’t take licenses away but will hit this lower limit through attrition and normal home sales. The maps tell a story that brings people together, informs the regulators, and helps planners and those furnishing services execute their work better.

As one of the elected officials responsible for refereeing these hotly debated issues, Lawrence closed the conversation by coming back to where she started. “Data is the key to everything we do. Without this data it would be really difficult to show people what is happening,” she said, “and to be able to overlay other services such as bus stops and environmental concerns gives us a much more complete foundation for our decision-making.” As one of the most popular STR areas in the country, many other vacation destinations are looking to Summit as a leader in this burgeoning field.

This story originally appeared in the April/May issue of Government Technology magazine. Click here to view the full digital edition online.