Echols is wrestling with the same question as others in government circles. How can they use technology to make information more readily available to the public? Should civic entities build downloadable apps for smartphones and tablets, or use responsive design to create mobile-friendly websites?

Her short answer is responsive design, with 85 percent of the county’s sites already converted to this mobile-friendly infrastructure and more under construction. But this hardly resolves the debate. Sacramento County also has downloadable apps to deliver polling place data, 311 functions, food facility inspections and crime reports.

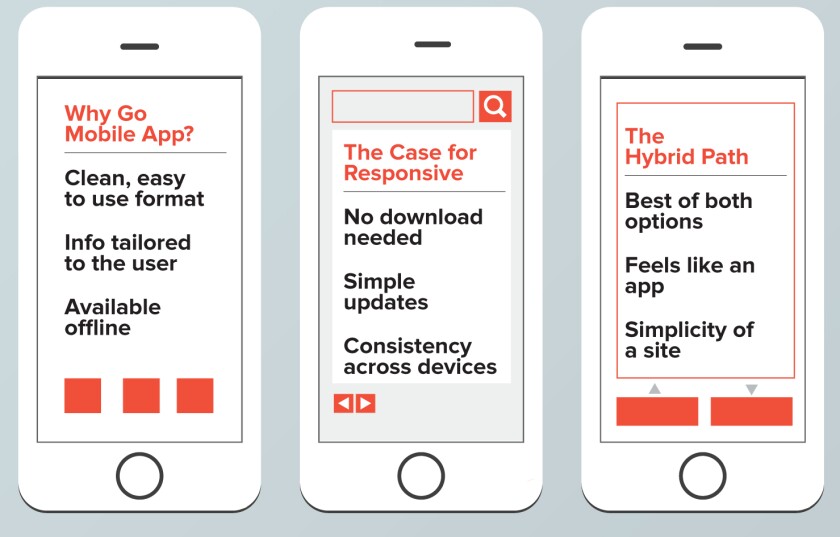

It’s a fairly typical scenario. Following the initial excitement surrounding downloadable apps, city, county and state governments are pulling back. They are turning more often to improved tools for responsive design, while still adding some native app functionality. They also are implementing hybrid constructions as a compromise, structures that allow for more mobile access while reducing the risks that come with smartphone apps.

RESPONSIVE SOLUTIONS

Not so long ago, apps seemed to be the answer to mobility, a way to get data to the masses in a clean, easily accessible format. Now improvements in the tools of responsive design have swung the pendulum the other way.Responsive design relies on a combination of flexible grids, adaptable layouts and scalable images. As users access a site using any of the various devices available today, the website adapts automatically to allow for appropriate resolution, image size and scripting, thus making for easy viewing on any device.

“When mobile apps were new, there was a certain buzz attached to creating them. There was a rush to have an app just because it could be done,” said West Virginia CTO Gale Given. “Today we see browser-based technologies catching up and being able to provide much of the same functionality as native apps.”

Sacramento County is turning to responsive design to meet citizens’ mobile needs, says E-government Chief Kristin Echols. Photo by Jessica Mulholland.

Through the state’s digital government program, Given’s office has designed 32 mobile-friendly applications on West Virginia’s portal. These include Financial Disclosure Filing, a State Phone Directory, Driver’s License Reinstatement Fee, Nursing Advanced Practice Application and a host of others.

Sometimes a website is simply easier to access than an app. Users tap into a dot-gov portal and click through, no download necessary. “The more information we can get to our constituents when they start that search, the better it is for everyone,” Given said. “A responsive Web application is just going to reach more people on the first shot.”

Such virtues are one half of the equation pushing responsive design. At the same time, many planners are driven to responsive design by what they see as the potential drawbacks of a native app.

Apps clutter a phone. “Everybody wants a presence on your home screen. Target wants to be there; Walmart wants to be there. What is the user going to choose? If you use Facebook every day, you want that on your home screen, but if you pay your taxes once a year, then you aren’t going to want that,” said Danny Straessle, the assistant public information officer at the Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department.

If people aren’t going to use it, why go through the expense — and the complexity — of building it? And it can be awfully complex. “When you look at all the different operating systems, all the different devices with their different screen sizes, that’s a lot of testing that you have to do whenever a new software version comes out,” said Ian McQuinn of West Virginia Interactive, an NIC company that operates the West Virginia state portal.

It’s a point that comes up all the time among civic IT planners. Devices come in so many sizes, systems and flavors, the prospect of keeping native up to date is just plain daunting, as apps must accommodate all these variables on an ongoing basis. This looming multi-platform threat is perhaps the strongest argument in favor of responsive Web pages.

It’s a technology challenge and also a personnel burden. Since 2008 the Los Angeles Information Technology Agency (ITA) team has lost 40 percent of its staff due to budget cuts, making rolling updates to smartphone apps a real challenge. “We don’t have the luxury to maintain all of this, so we have to be very smart about how we do this,” said Ted Ross, assistant general manager of ITA’s Technology Solutions Bureau, an office with 175 people and a $32 million annual budget.

So the argument for responsive design is strong — but that doesn’t mean apps are dead.

THE CASE FOR APPS

While app developers may be hard to come by, there is a flip side: Many managers have found that talent is similarly lacking to make websites mobile-friendly. In Westminster, Colo., Information Technology Director David Puntenney promoted an internal IT expert into the mobile guru spot after an unsuccessful search for a mobility pro. “We posted that job announcement once at the end of last year and once at the beginning of this year,” he said. “And we were not successful in finding a candidate that had the qualifications we were looking for.”In Los Angeles, Ross still sees a place for smartphone apps in the civic cosmos. The city offers citizens the MyLA311 app on Apple and Android. The app provides information on a range of city services and is in the midst of an upgrade, with planners installing a function that will notify citizens when a problem is solved.

Why go native? Ross and others note that some apps may rely heavily on a phone’s functionality, for example by making use of the camera or the geocoding capability.

A phone app also can be tailored for personal use. “Suppose you enter a library and the app could push a message that says this library has an event on Saturday,” Ross said. “Then suppose you can change the settings within your app to reflect who you are and what you want to get out of the service.”

Apps can help, too, when a user needs to access data even when out of signal range.

In Arkansas, the emergency management department runs an app chock full of critical response data. Should rescuers lose their connection to the network, they’ll find that information in a mini website embedded in the app. “If there is a major disaster and the cell network is down, how else are you going to get to this information?” Straessle said.

Apps also have an air of legitimacy. It sounds a little bit counterintuitive: Certainly a government website ought to be a trusted source of information, and even more so if it responds smoothly in a mobile environment. But there’s something about the user experience that makes an app feel more solid. Imagine poking around your bank’s website looking for the login somewhere on that front page, versus firing up an app that opens at the login page and goes right to the three or four basic functions you need.

User familiarity counts, and users have become accustomed to the app experience.

MIDDLE GROUND

While there are pros and cons on both sides, it’s not hard to tell which way the wind is blowing. Winston-Salem, N.C.’s 311 smartphone app launched in January 2013. Arkansas’ driver information tool began downloading in summer 2013, L.A.’s citizen info application launched in early 2013 and Sacramento County put its 311 app into play in October 2013.Apps are so two years ago. That doesn’t mean that responsive is the only solution, however. In fact, many technology planners are turning toward a third option, the “hybrid” app, as a way to enable mobility with the fullest possible access for all.

As the name suggests, hybrid apps combine advantages from both the Web-based and native app environments. A hybrid app may be thought of as a core of Web information, wrapped inside a smart-phone shell. It looks like a downloadable app and delivers like a responsive website.

The hybrid proposition is intriguing on a number of fronts. First, these apps can be downloaded from an app store. They look and behave with a familiar app cadence, something designers are eager to deliver to end users.

e.Republic

finding suitable IT talent. In addition, these apps are easier to maintain, with upgrades to devices and systems handled in one fell swoop, rather than on a rolling basis of one-off adjustments.

A hybrid can offer access to Web content, paired with a smartphone’s functionality. Driven by the “app” shell that surrounds the core content, the hybrid can tap into the camera, geolocator and other device-specific features. Since they are available through app stores, hybrid applications are easily discoverable by users. In 2013 Gartner predicted that by 2016 more than half of all mobile apps deployed would be hybrid.

Puntenney calls this a tempting proposition. His office has received requests for 70 functions from various departments, and it’s likely that a fair number of those will be fulfilled, not by mobile-ready Web pages or downloadable apps, but rather by some hybrid solution.

“It would allow us to develop and manage an application in an HTML5 environment,” he said. “So it would be easier for us to keep that up to date, while we would still be able to take advantage of the capabilities of the device.”

So far Puntenney has identified a few possible candidates for a hybrid solution, and he’s looking for more.

Another example comes from IDrive Arkansas, an app that lists road closures and traffic conditions. It also offers maps and gives drivers a way to report problems. Users download the app onto their phones, but it isn’t really there.

“It basically puts the icon on your home page, and then when you click on it, it launches the site. Then when you do launch the site in mobile, it looks and feels like an app,” Straessle said. The ease of an app-like interface matters in this case since those using IDrive will likely be … driving. The more they keep their eyes on the road, the better.

“We know it is easier for someone to go to the App Store or the Google Play store and just download the app, as opposed to typing in a URL. ‘Idrivearkansas.com’ is a lot of text that runs together,” Straessle said. With the hybrid solution, users get ease of access, without all the surfing and clicking.

IDrive has seen 73,000 downloads, making it the state’s second most popular app after a game-and-fish tool.

Hybrid could eventually solve the kinds of technological complications Given faces in West Virginia. For example, she’d like a way to add something as simple as a new highway rest stop to a directory without having to do a full re-release of an app. A hybrid’s site-within-an-app arrangement might facilitate that.

It may well be that hybrid is the wave of the future in government mobility, but until that wave crests, IT planners say responsive design likely will be the tool of choice. It’s easy to build and update, it makes data simple to find and access, and tools like HTML5 mean it can be done without a lot of specific mobile expertise.

Whatever route one chooses, government planners say the bigger point may not lie so much in how one goes mobile, but in whether one is committed to going mobile at all.

“There is so much opportunity to enhance our service delivery through mobile,” Puntenney said. “You hear the term ‘mobile first,’ and really anytime a new application is going in, we do need to be considering the mobile requirements up front, so we are building that to meet mobile needs right from the beginning.”