Parents are often unaware. Teachers and school IT professionals are often too busy to provide more privacy protection oversight.

School districts, meanwhile, typically welcome the free-to-use technology provided by for-profit companies, given that budgets are often stretched to their breaking points and the apps, software and even computers can provide vital 21st-century learning experiences.

“As is often the case with K-12 education, one of the biggest challenges is having adequate resources available for schools to comply with compliance requirements and stay on top of different risks and threats,” David Sallay, a former chief privacy officer for the Utah State Board of Education who now works for the data privacy nonprofit Future of Privacy Forum, told Government Technology.

But as the pandemic slides into the history books — COVID-19 sparked a quick need for the latest ed tech — those privacy issues are coming into clearer focus and gaining more attention from educational groups, advocates, government agencies and lawmakers. Best practices about how to better protect student privacy are starting to emerge as the realization sets in that ed tech will continue to grow with or without the sustained need for remote learning.

ED-TECH EXPLOSION

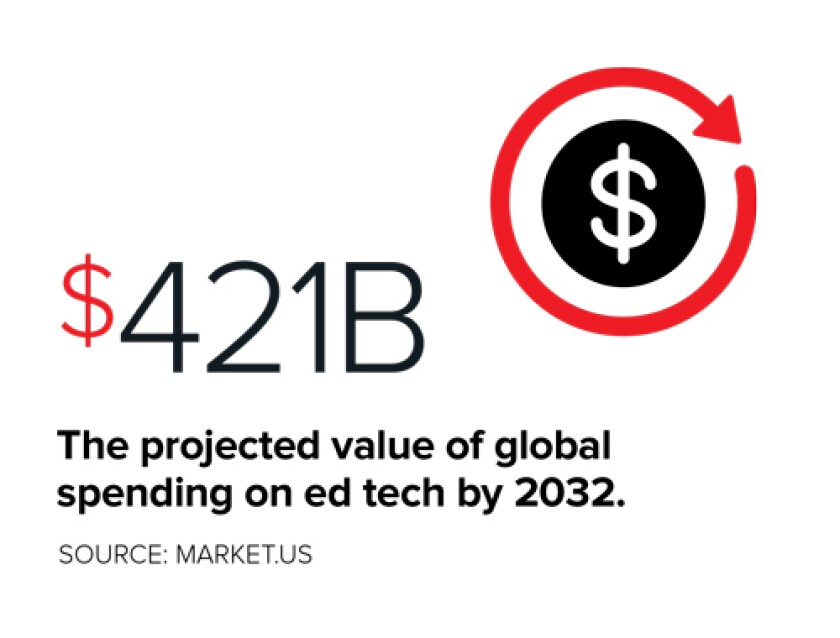

On average, students today use more than 140 ed-tech tools during the school year, according to recent research from North Carolina-based ed-tech company LearnPlatform. The most common tools include Google Suite, YouTube and Kahoot!. Even more ed-tech tools promise to hit the market over the next decade or so. One recent market report estimated that global spending on educational technology will reach $421 billion by 2032, a compound annual growth rate of 12.9 percent.

“With tech-enabled learning here to stay, understanding which tools are both effective and safe will not only improve teaching and learning, but help budget decisions as districts face a fiscal cliff as stimulus dollars are spent, too,” LearnPlatform co-founder and Chief Executive Officer Karl Rectanus said

in a statement.

More ed tech promises more risk when it comes to student privacy and breaches — and that risk is already meaningful. For instance, nearly 100 student data breaches were tallied between 2016 and 2020 by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, according to another recent study.

Then, in early 2022, ed-tech firm Illuminate Education suffered a data breach; free lunch, special education and other data for more than 800,000 current and former New York public school students was compromised.

Illuminate has since been acquired by Renaissance, a major provider of K-12 ed-tech tools, and while Renaissance officials would not offer detailed comment about the breach because of “ongoing litigation,” a spokesperson said that Illuminate immediately took affected systems offline and notified potential victims by July 2022.

Another cautionary tale comes from the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC), charged with enforcing the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) and similar laws.

The agency sued California-based ed-tech supplier Edmodo — its free and subscription online platform and mobile app hosted virtual class spaces and discussions, and enabled the sharing of materials and other tasks — because, the FTC said, the company’s collection of student email addresses, birth dates, phone numbers and other data that was then used to craft and deliver advertising was a violation of COPPA.

The law requires Edmodo and similar companies to notify parents, schools and teachers about data collection and obtain parental consent for the data’s noneducational use. Earlier this year, the FTC proposed a $6 million settlement order.

Edmodo, which once served as many as 600,000 students in a single school year, is now out of business and would be unable to pay the settlement, the federal agency said. But the FTC wants to send a warning to other ed-tech firms and otherwise raise awareness of student privacy protections.

In the wake of the FTC’s action against Edmodo, some experts are now questioning a major part of the ed-tech business model.

“It is a big question as to whether any type of marketing will be allowable, at least toward young children,” Sallay said. “That is going to really challenge the business practice of offering free versions to teachers that are paid for with advertising until the school pays for an enterprise version that is ad free.”

Talk to student privacy experts and it’s easy to hear praise for the FTC’s actions against Edmodo, even if they are often mixed with criticisms that amount to “Well, what took you so long?” The federal agency, after all, is signaling that it will make ed-tech companies more responsible for those protections, not parents, not teachers and not schools.

Ed-tech and associated privacy protections reflect a “power imbalance,” said Sophia Cope, senior staff attorney for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit digital rights group. Free technology — and the so-called freemium model — are “very attractive to schools, especially public schools, because they are underfunded.”

And, she added, those tools can serve important purposes such as an increase in cloud storage and better email, to say nothing of the direct learning features that might do a better job of engaging tech-savvy students than relatively clunky software or analog tools.

But in exchange for that, school districts are typically put in a position where they have to accept the terms of service as is, without modification or negotiation.

There are also relatively few direct relationships between schools and the suppliers of free ed tech, further weakening the position of school districts and putting students in situations that can potentially be tense or painful — perhaps, Cope said, by flagging LGBTQ content that would essentially out a student without their consent.

But the FTC’s recent actions on student privacy could lead to changes, to ed-tech companies better conforming to privacy expectations and even innovating along those lines, Cope said. Schools, in turn, could be “pickier” about what free technology they use, which would likely encourage entrepreneurs to work more closely with them to protect against misuses of student data.

Of course, Cope pointed out, states might resist the federal government dictating too much when it comes to education or even the enactment of a new nationwide privacy law. One obvious obstacle: States and local governments fund most public education, with the U.S. federal government chipping in an estimated 8 percent.

STATE AND LOCAL EFFORTS

States also havetheir own protections and programs. Indeed, most have passed or are considering student privacy laws, though experts say the majority of those protections apply to public schools, not private ones, according to one survey.

School districts are also taking their own actions to balance ed tech with student privacy protections.

The Fairfax County Public Schools in an affluent part of Virginia stands as one example, at least according to the experience of Jim Siegl, who from 2002 until late 2020 was the district’s technology architect, during which time he focused on privacy, security and other issues.

For starters, he said the district had a standard policy for ed tech that covered technology requests, vetting and approvals, and revolved around “determining if the tool was a good instructional fit, rather than starting with the technology,” he said.

School tech staff also communicated about what tools were approved and made that list available to students, parents, staff and teachers.

“We had a strong governance process that brought the technology and instructional groups together on a regular basis to make decisions about major systems like Google Workspace,” Siegl said, noting that Fairfax is an atypical district because of its large size. It operates nearly 200 schools and has more than 180,000 students.

Even so, he said, “the steps that my colleagues and I took to protect student privacy are broadly applicable.”

This story originally appeared in the September issue of Government Technology magazine. Click here to view the full digital edition online.