And although mass shootings, including those at schools, are still relatively uncommon, they have become predictable and unsurprising when they happen. The usual arguments ensue until the next rounds of ammunition are fired into innocent, unsuspecting folks.

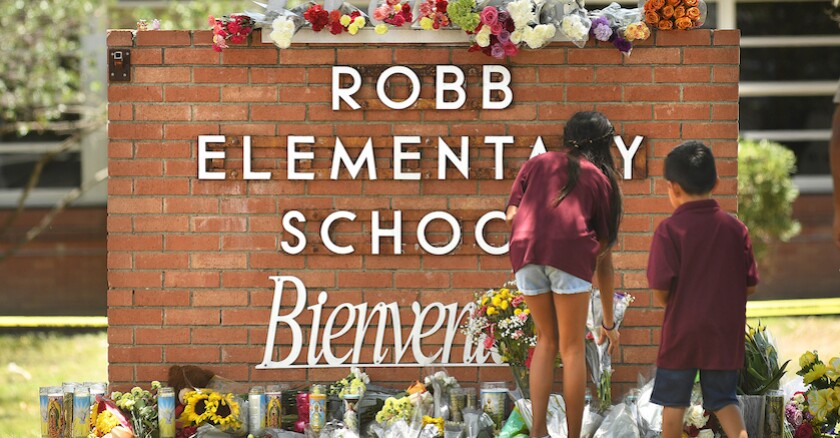

This time it was 19 students and two teachers at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, who were the sitting ducks at the hands of a newly armed gunman.

And let’s not forget that another angry 18-year-old killed 10 people at a Buffalo, N.Y., grocery store less than two weeks ago.

Of course, in the case of murders at school, there are variables that make it hard to stop, such as the difficulty in securing school campuses, the availability or not of school resource officers (SROs) and the lack of funding to take these steps.

Even with any of these measures in place, it’s hard to stop someone with an automatic rifle bent on destruction, whether there is an armed officer or teacher on the premises or not. “They’re challenging to stop, there’s no question about,” said Mo Canady, executive director of the National Association of School Resource Officers.

“When someone wants to kill someone, we know from law enforcement that murder is one of the most difficult crimes to stop unless you can intervene somewhere along the way," he said.

The country is now grappling with how to intervene into what is really an American problem.

The New York Timesran a chart yesterday that showed that, indeed, the United States is easily the leader in mass shootings, with 101 between 1998 and 2019; France comes in a distant second, with eight in the same time period.

“It’s not a normal situation for a country of our size to have 400 million weapons at the hands of civilians,” said Richard Hamburg, executive director of Safe States Alliance, a national nonprofit and professional association of injury and violence prevention professionals.

“I was looking at a stat from the U.K. yesterday,” Hamburg said. “They haven’t had a school shooting in 25 years. This country is unique, and not in a positive way, regarding access to firearms and lethal assault weapons, that it’s that easy for a troubled teen to celebrate his or her 18th birthday by going to a gun shop and buying high-capacity firearms.”

It’s become a public health issue, just as tobacco before it, and car safety, among other things. Certainly mental illness is one of the variables, but that’s a given, low-hanging fruit, Hamburg said.

“The idea that the first response of many policymakers is ‘We’ve got to get these guns out of the hand of the mentally ill,’ well yeah, but that’s not it. We have to get guns out of the hands of those who shouldn’t be carrying automatic rifles and have easy access to schools.”

And the availability of firearms is getting worse, as some states now allow people to carry concealed weapons. And that means, Hamburg said, people will leave them in their vehicles where they are easier to steal, when safe storage at home is a no-brainer.

“This should be prioritized and called a public health approach to gun violence prevention — better education, training. When it’s harder to get a whole lot of things in life than a firearm, that’s unfortunate,” Hamburg said. “It’s this many being injured and dying that truly makes it a public health crisis. How can you not support adequate programs for registration, background checks?”

He pointed out that the tobacco companies had their way for decades, selling tobacco and killing people, until years of education finally took hold. The safety of motor vehicles took a similar trajectory when policymakers realized they could drastically save lives with seat belts, air bags and lower speed limits.

In this case, some of the variables around gun violence prevention include the registration of firearms, background checks, bans on assault weapons and high-capacity magazines, and effective implementation of extreme risk protective orders. “This was clearly an example of someone who should not have had a gun, who was known to have some issues," Hamburg said.

Of course, Canady is an advocate for having SROs on campus, which Robb Elementary in Uvalde didn’t have. He said SROs alone can’t solve the problem, but it is a viable layer of protection among others, including limited entry onto school grounds.

“You and I can walk up to just about any school in the country and knock on one of those perimeter doors and somebody is going to open it,” Canady said. “So that’s a problem."

He said he has always been an advocate for single point-of-entry in a school that is controlled by an administrator. “Now obviously you have all the perimeter doors secured and people unable to enter from the outside and that sounds simple, but there are a lot of challenges that go along with that.”

Maintenance of the doors is a problem, convenience is a problem and people will leave the doors propped open or open them for friends or strangers. “So there are a lot of issues there,“ Canady said, “and while it sounds simple, there are too many human variables.”