The day before, she heard the gunshots.

The gunshots that left two of her cousins dead — and two other cousins injured — after the gunman entered the school through the back door and shot up a classroom.

The young girl hasn't slept much since, still hearing the pop of the shots and feeling the terror. But she still managed to deliver the Teddy bear to the memorial, sobbing into her mother's body as she explained her sadness. Her 6-year-old sister Kinsley gave her a hug.

"How do you comfort a child that's broken?" asked her father, Mark Madrigal . "All you can do is hold them."

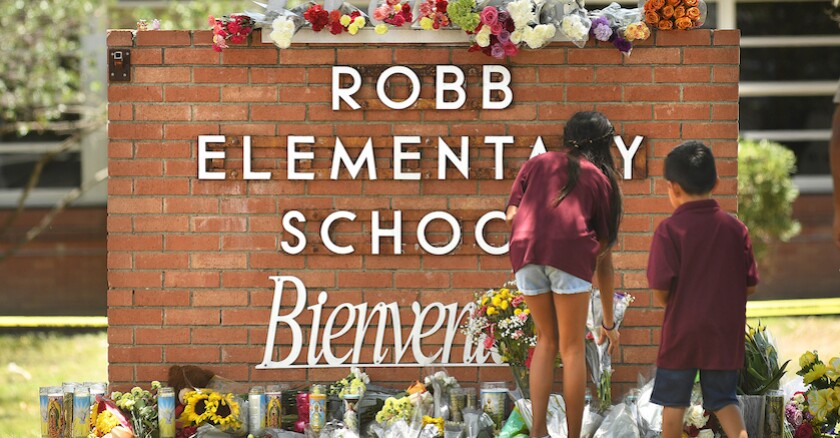

It was just one example of the reality of a horrific massacre sinking in for this grieving, small community. Nineteen children were dead. Two teachers were killed. Seventeen other people were injured. Uvalde, a quaint city with roosters in yards, was now swarmed with law enforcement officers, reporters and high-ranking public officials.

The 18-year-old gunman, Salvador Ramos, the day before carried out the deadliest school shooting in Texas history. Details that emerged added to the horror, as volatile political perspectives clashed over how to prevent another mass shooting from happening in the pro-gun state.

"Evil swept across Uvalde yesterday," Gov. Greg Abbott said at a mid-day news conference in town. "Anyone who shoots his grandmother in the face has to have evil in his heart. But it is far more evil for someone to gun down little kids. It is intolerable and it is unacceptable."

Salvador Ramos , who officials said was a high school drop out, on Tuesday morning shot his 66-year-old grandmother with whom he lived. She ran to her neighbor's house. She called the police. Ramos wrote in a private message: "I'm going to shoot an elementary school," authorities said. He drove his grandmother's vehicle maybe a block-and-a-half toward Robb Elementary, where he crashed it.

Ramos then grabbed his backpack and an AR-15-style semiautomatic rifle and headed for the school's back door, engaging with a school resource officer on the way. No shots were fired. Ramos entered the school. The officer followed him. He turned right. He turned left.

It was awards day for the kids.

Students watching the Disney movie "Moana" heard several loud pops and a bullet shatter a window, recounted Dillon Silva, whose nephew was in a classroom, to the Associated Press . Ramos entered one classroom, which adjoined another.

"That's where the carnage began," said Steven McCraw, director of the Texas Department of Public Safety, sharing the details of the crime at the news conference alongside Abbott.

A day later, it was impossible to make sense of the violence Wednesday. Officials named no motive. The only clear message was how horrible it was. People in this southwest Texas city had no choice but to keep moving through the emotions.

Abbott and others praised the reaction from first responders, but 21 people had died, and everyone had to grapple with that.

"I want to wake up and just think, 'It's a dream. It didn't happen,'" said 60-year-old Pat Martinez, who anxiously sped to the school to find her 8-year-old grandson in an evacuation area. She cried when she saw him. She woke up the next day still crying and with a headache. She got herself up for breakfast with a friend and headed to work.

Three of Martinez's friends lost kids. Everyone in Uvalde seems to know someone affected, maybe from their days as a student, or time spent at the gym, or Sunday mornings in church. Community businesses became part of the healing: A florist filled orders at rapid-pace. Funeral homes offered services free of cost.

Relatives mourned those they lost, posting images of the kids on social media and sharing stories. There was a boy who loved to ride his bike. A girl known as the loudest cheerleader on her basketball team. A grandson still learning football pass patterns with his granddad.

One mother celebrated her daughter that morning before she died for making the all-A honor roll, she wrote online. She thought she'd be back to pick her up from school.

"Please don't take a second for granted," a father wrote. "Hug your family. Tell them you love them."

Others injured were still being treated Wednesday morning at higher-level trauma hospitals 85 miles east of Uvalde in San Antonio. They included the gunman's grandmother, two other adults and four children. Statements from Brooke Army Medical Center, University Hospital and Methodist Hospital described the patients as in serious, good and stable conditions.

Journalists heard screams and cries Tuesday night as parents learned the news about their kids at the civic center. On Wednesday morning, when counselors were scheduled to be on hand there, someone walked inside with two bags full of tissue boxes. Others embraced in the parking lot. The flags flew at half-mast. The crime scene was taped off and the roads were blocked.

At the Herby Ham Community Center , residents formed a long line to give blood, wanting to find some way to help.

"Nobody knew of Uvalde," said Caycee Felan, 28, "and sadly now everyone knows of Uvalde."

The national conversation was hyper-focused on the city, as politicians, advocates and celebrities sparred over what policies need to change to prevent another such disaster. Abbott at the press conference said an 18-year-old could by long guns legally for more than 60 years and suggested more needs to be done to address mental health.

When Abbott prepared to pass the microphone to Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, Democrat and gubernatorial hopeful Beto O'Rourke approached the stage, pointed at Abbott, and said, "This is on you."

"You're out of line, and an embarrassment," Patrick said.

Uvalde Mayor Don McLaughlin, standing onstage behind Abbott, fired out an expletive.

The National Rifle Association meanwhile still plans to host its annual meeting this weekend in downtown Houston , at the George R. Brown Convention Center . Former President Donald Trump and Abbott are both scheduled to speak. Mayor Sylvester Turner said he could not cancel the event because the city was contractually obligated.

As the sun lowered Wednesday in Uvalde, hundreds gathered in the county fairplex, filling the bleachers to pray for healing, unity and answers they might never get.

This is the kind of place where everyone is united, those who live here say, where everyone knows everyone if nothing else because they have kids who go to the same schools.

"It's very hard to understand," said Julio Garcia, a 44-year-old father. "It affects us all."

Photographer Jon Shapley and reporters Alejandro Serrano, Jeremy Wallace, Monique Welch and Nora Mishanec contributed to this report. San Antonio Express-News reporters Laura Garcia, Emilie Eaton , Jacob Beltran and Annie Blanks also contributed. Further reporting was pulled from the Associated Press.

©2022 the San Antonio Express-News, Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC