Risks include everything from fine-tuned disinformation campaigns to blackmail attempts against Americans in influential positions, said Sen. Chris Coons, D-Del., who convened the hearing.

“Hostile foreign intelligence services continue to work to gather sensitive information about each and every one of us. They collect information about to whom we speak, the places we visit, the news we consume, the products we buy, and a great deal more,” Coons said. “The insights buried in that data can be used against us.”

Matt Pottinger, chair of the China Program with the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, said that the Chinese government has required social media firms in the country to share insights with it about how their news feed curation algorithms work. Such insights might help political leadership manipulate the news feeds of users worldwide.

“The autocratic regime in Beijing now regulates the AI algorithms that are the secret sauce in Chinese-owned social media apps that are becoming dominant in the United States and around the globe,” Pottinger said.

Using an online service or digital device leaves digital footprints, and Pottinger warned about risks related to broader collections of such data.

“The data that's been accumulated in aggregate gives important demographic information to the Chinese government, about public opinion and how to predict popular topics, and how to, therefore through those popular topics, manipulate public opinion,” Pottinger said.

Adam Klein, director of the University of Texas at Austin’s Strauss Center for International Security and Law, raised similar concerns. He said the Chinese government could, hypothetically, craft specific political narratives and spread them over social media apps where it has sway — something that would be particularly detrimental should the U.S. eventually find itself at war with the country.

“[Algorithms] could potentially be tweaked to amplify pro-China messaging, pacifist messaging, messages that might send panic through the American population in the event of the war,” Klein said.

HOW COUNTRIES GET DATA

There’s plenty of ways for other countries to collect data on Americans, ranging from hacking to requesting or demanding it from companies that have gathered it on their customers, to simply buying it from data brokers. Combining data from multiple sources can give recipients detailed insights.

The Chinese government, for example, can often get data from companies within its borders. That includes placing backdoors inside hardware and software to access data on users, said Sen. Ben Sasse, R-Neb.

Pottinger spoke similarly: “The cooperation between nominally once-private companies in China and the Communist Party is becoming systemic,” he said.

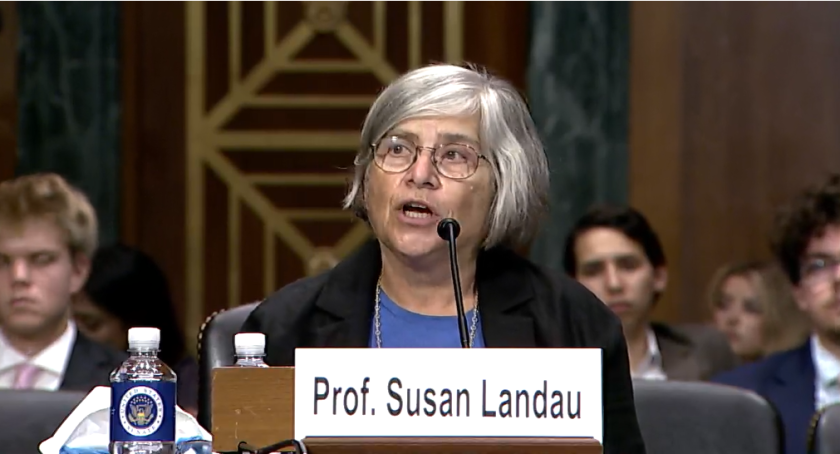

Vast amounts of American data can also be purchased from data brokers, which collect and sell detailed information, including metadata and device telemetry, said Susan Landau, bridge professor in cybersecurity and policy at Tufts University.

“China doesn't need to go through the backdoor to get personal data on Americans. We've opened it up through the front door,” Landau said. “Users are tracked from the moment they pick up their mobile device in the morning till they lay it down at night.”

HOW DO WE CHANGE THE PICTURE?

The U.S. can’t do much about the data countries have already gathered, noted Sasse. The nation is also unlikely to be able to stop all data gathering by its adversaries, Klein said, but it can make doing so harder and more resource-intensive.

“People might say, ‘Well, if the data is stored overseas or in loosely secure data centers, they [adversary countries] can still find a way in,’” Klein said. “That's true, but let's make them work for it. Let's make them, for example, send a human intelligence officer to a third country and try to gain access to a data center. That's a lot harder than simply bringing it out through an app or buying from a data broker. Let's force them to burn some zero-day vulnerabilities to get into these treasure troves.”

Improving the situation can include both finding ways to better control data sharing with other countries, as well as ways to keep data more private and protected in general.

Even if the U.S. forbids selling data to specific nations, it cannot guarantee the countries won’t find ways to buy or steal it. That makes an across-the-board data protection policy key, said Samm Sacks, senior fellow at the Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center.

“Congress should mandate basic standards for what data can be collected and retained in comprehensive federal privacy law to protect U.S. data regardless of where the risk originates,” Sacks said.

Developing and promoting strong encryption methods would also help keep data private even if it’s transmitted to an adversary country, Sacks said.

Landau recommended ensuring that a proposed federal privacy law, the American Data Privacy and Protection Act, specifically restrict use of telemetry and metadata. Use of such sensitive data could be limited to purposes like maintaining communication network security, public planning and research benefiting the public interest — not for sale to digital advertisers.

A stronger privacy approach could also foster greater international collaboration, by bringing the U.S. into greater alignment with the European Union and Japan, Landau said.

“The U.S. needs to develop a tailored data-denial strategy to curb the flow of sensitive U.S. and ally data to China that can be exploited by the CCP [Chinese Communist Party],” Pottinger said.

At the same time, several speakers said there are benefits to sharing data with allies, which should be preserved.

“Open data flows between the U.S. and our allies and partners around the globe have been critical to economic growth and innovation,” Sasse said.

On the one hand, a fragmented global Internet “dominated by data localization” would impede innovation and commerce, Klein said. On the other, the U.S.’ traditional goal of “global borderless” Internet now poses too many security risks. He said the U.S. needs a new vision, and he and Pottinger both pointed to former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s Data Free Flow with Trust (DFFT) concept as a promising idea.

According to Pottinger, “[In essence it] says countries that … want to work within an environment where the rule of law is respected, where privacy is respected, should be pooling data in ways that make that data useful,” while restricting data flows to countries without such policies.

The NYU School of Law’s U.S.-Asia Law Institute explains that the DFFT approach aims to encourage interoperability among countries' data protection frameworks, in ways that let sending countries transfer data without fear that doing so will undermine their policy goals, while recipients avoid overly burdensome requirements.